Cracking the case with Detective Pikachu.

A few months ago, I wrote a blog that briefly addressed the limitations and potentialities of Detective Pikachu (2016 video game) as an “adaptation” of Sherlock Holmes. Recently, I watched the film adaptation of the game, and although I found it entertaining, I’m still puzzled as to the connection between Detective Pikachu and Sherlock Holmes.

Much has been said about the Holmes-Pikachu collab by Sherlockians and fans of Pokémon alike. Paul Thomas Miller sarcastically refers to Detective Pikachu as “the most canonical Sherlock ever and definitely not just a pokemon in a hat,” and fellow Sherlockian and author, Brad Keefauver, wrote an insightful blog about how the film can be interpreted as a John Watson story rather than a Sherlock Holmes story. I’m adding to this ongoing discussion about the film by comparing it to my experience of having played the game, and to argue that the film adaptation works to further distance itself from the world of Sherlock Holmes rather than paying an homage to it.

Here’s why:

1) The dynamic duo Holmes/Watson is undermined in the film compared to the game.

In my previous blog, I mentioned that one of Tim’s main tasks in the game is to provide illustrations of the crime scene, which are used to help the player decipher and solve mysteries. This method of “note-taking” is similar to how Watson documents his adventures with Holmes in the canon, but it’s omitted in the film. This might seem like a minor detail, but I think it’s an important aspect of Watson’s role as Holmes’s chronicler. In BBC Sherlock, for example, John Watson blogs about his adventures with Holmes, and in other stage/cinematic adaptations that feature the duo, Watson is often shown writing in his journal. There are similarities between Holmes/Pikachu and Watson/Tim, but with respect to Tim’s role as a chronicler, the Hollywood blockbuster chooses to leave out this detail.

2) Who’s the “world-class detective,” Pikachu or Harry?

In the film adaptation, Harry survives the car accident thanks to Mewtwo’s mind transfer technique, and at the end of the film, he is reunited with Tim and his partner Pikachu (who apparently loses all memory of his adventures with Tim). However, the answer to the question of whether Pikachu is Tim’s father in disguise is left ambiguous at the end of game as the crime-solving duo continue their search for Harry Goodman (and for good reason). In other words, the film thwarts Pikachu’s role as a detective and demotes him to the role of Harry’s side-kick whereas the game leaves it more open-ended. If Harry is a world-class detective and if Tim is “Watson”...what’s Pikachu’s role in the future?

I’m Har…I mean Pikachu…a world-class detective

3) Do kids want to see the film because it’s an adaptation of Sherlock Holmes, or for Pikachu?

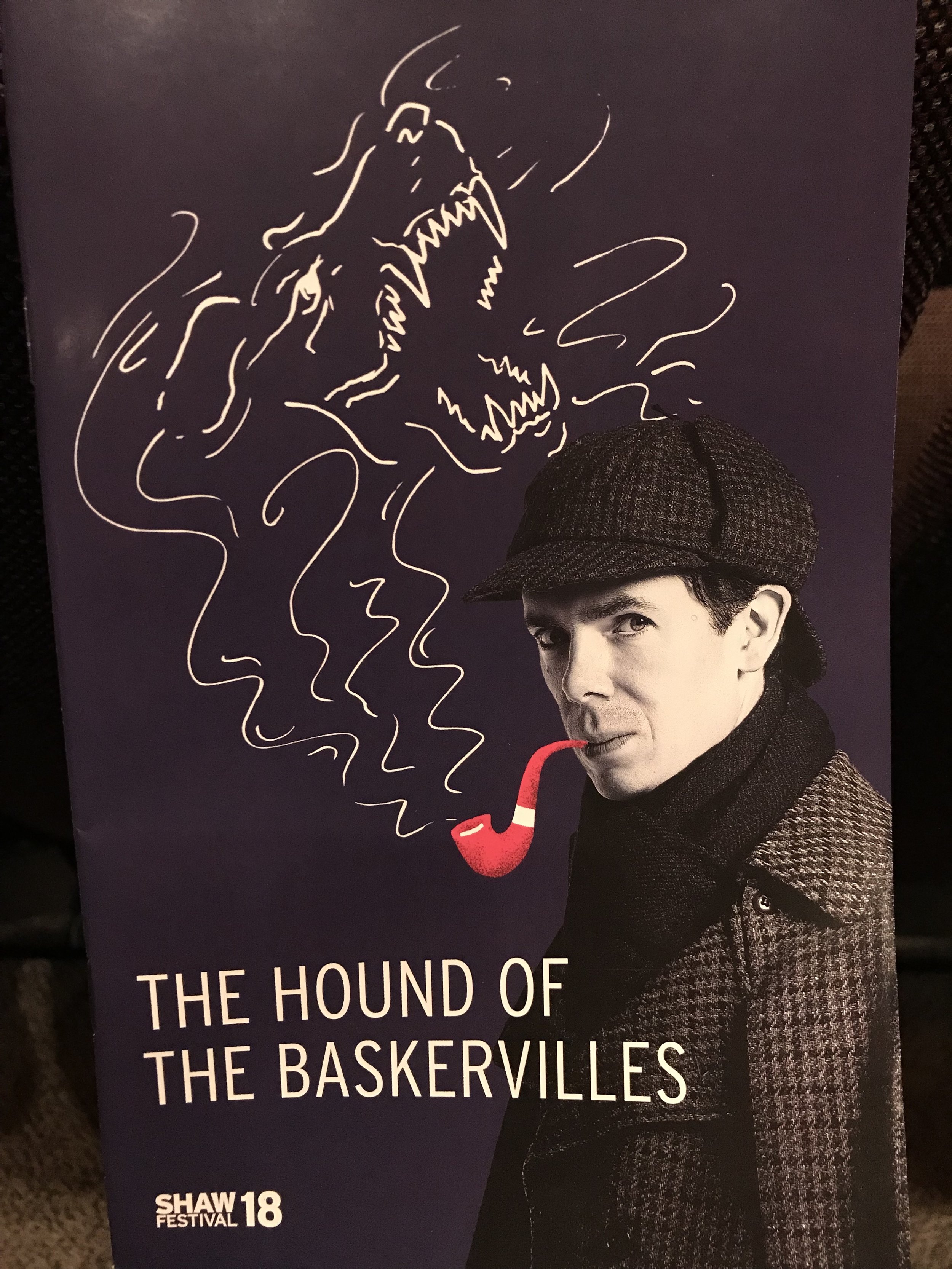

I raise this question because there are so few references to Sherlock Holmes and to the canon in the film. Most kids, with exception to those who have read Doyle’s stories, may not be able to draw the connection between Pikachu and the Great Detective/Watson based on the film alone. Yes, Pikachu wears the iconic deerstalker hat, and at one point holds a magnifying glass in Howard Clifford’s office, but these subtle allusions to Holmes highlight a superficial connection to Doyle’s Victorian sleuth (as I mentioned in my previous blog). In the game, Pikachu has the option of wearing a cape to complete his look, which is not included in the film version, but clothes alone do not make a detective as Rob Nunn points out, “a deerstalker does not make someone Sherlock Holmes.” Perhaps the film could have benefited from incorporating popular quotes that most people might recognize as part of the canon such as “the game is afoot,” or something along these lines, but that still doesn’t solve the issue…

As a fan and scholar of Sherlock Holmes, I can’t say that Detective Pikachu (film) is an adaptation of Doyle’s Holmes, but there are aspects that I think the film does a lot better than the game, especially in terms of showcasing an ethnically diverse cast, and for incorporating assertive female characters such as Lucy Stevens played by Kathryn Newton.

I agree with Keefauver that Detective Pikachu is not for all Sherlockians, and I think that’s because the film is not meant to be an adaptation of Sherlock Holmes or Watson. Instead, like the game, the film capitalizes on the visual cues of Sherlock Holmes (or things that people would associate with mystery and detectives in general such as a magnifying glass) as well as on the Pokémon franchise in order to profit from a broad, cultural audience. In other words, the film offers something for everyone, but in trying to catch’em all, perhaps it reaches too far and too wide.