Let’s see… if I had to summarize the past month in one word, it’d be: chaos (so much so that chaos is now the norm). The Covid-19 pandemic altered the course of what I had planned up to a year ago. With the cancellation of the Association for Asian Studies conference in Boston, the 2020 Conference on Postsecondary Learning and Teaching at the University of Calgary, and my students’ exhibit and some classes, just to name a few incidents, I felt that everything I had meticulously planned for and worked hard to achieve was slipping through my fingers. At least we have no excuses not to publish, since we can spend endless amounts of time at home pumping out great ideas while practising social distancing (ah yes, if only the libraries were open!). So, here we are, all stuck at home. Like Sherlock Holmes, “I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation” (The Sign of Four) because stagnation gets me nowhere. So, if you ever find yourself in a situation where everything seems to be falling apart because of things outside of your control, don’t take it as an opportunity to give up and snooze; re-strategize and implement a plan of action. Keep yourself busy and make things happen!

On April 1st, my students and I “curated” the first online “exhibition” in MLCS history on Instagram! (No joke.) The live exhibition was supposed to happen during the last two weeks in collaboration with students from another MLCS course. It was meant to showcase the works created by students for their final assessment and was meant to display all the “cool” stuff happening in our course and department. I had also planned catering, posters, banners and balloons (as well as a photo booth), but all of this went down the drain, or so I thought. If anything, having to adapt and deliver course content in non-traditional ways inspired me to think outside of the box. So, I took our Instagram page and made it into a space where students could still engage in peer learning and attend the exhibition virtually. The exhibit portion of our Instagram page showcases projects and posters that students created as part of their final assessment for this course. Students had the choice to either produce a traditional paper and a poster to accompany key ideas and themes explored in their essay, or to produce a creative project and write a critical reflection that explained the relevance of their work to the study of popular culture.

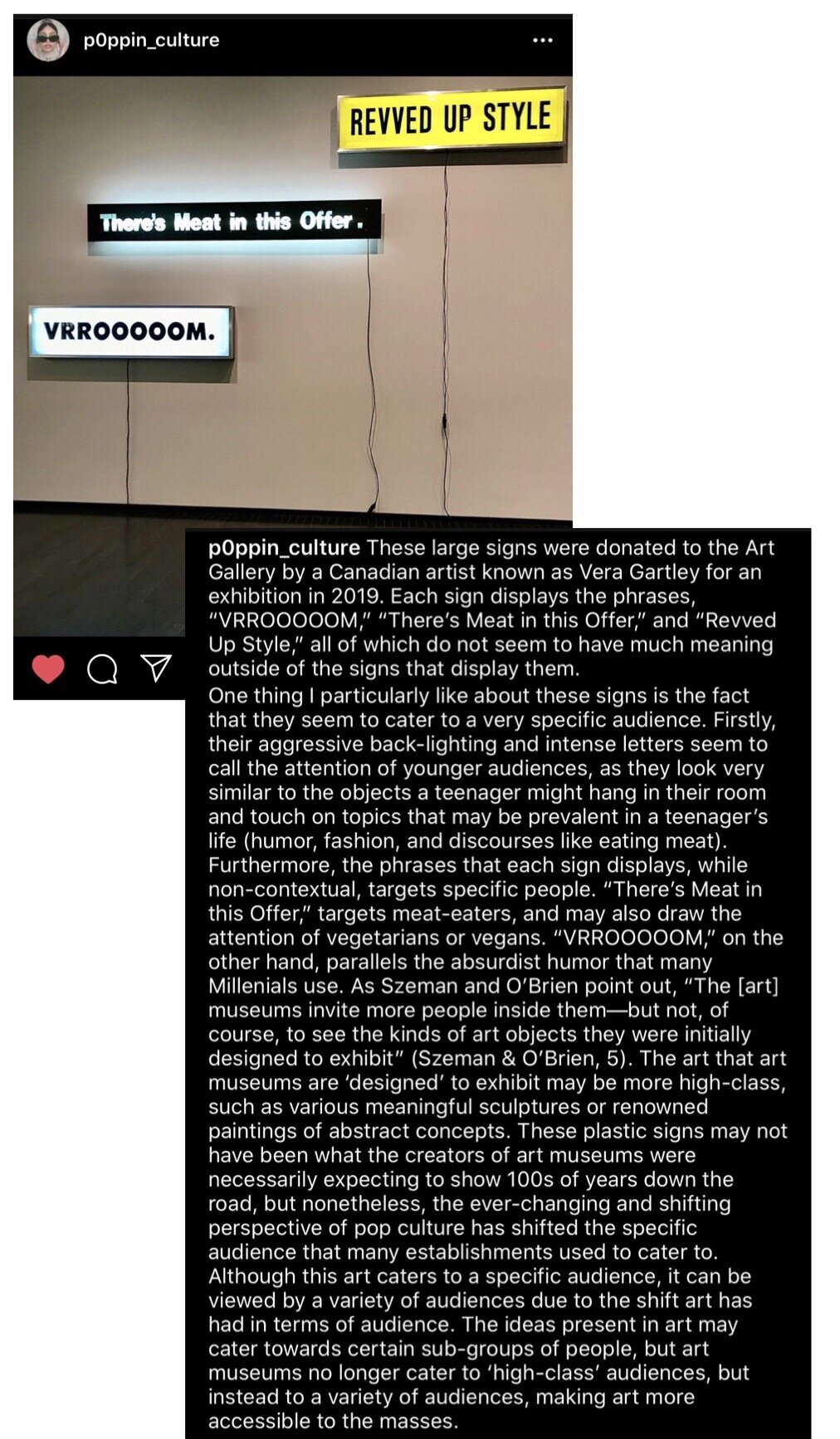

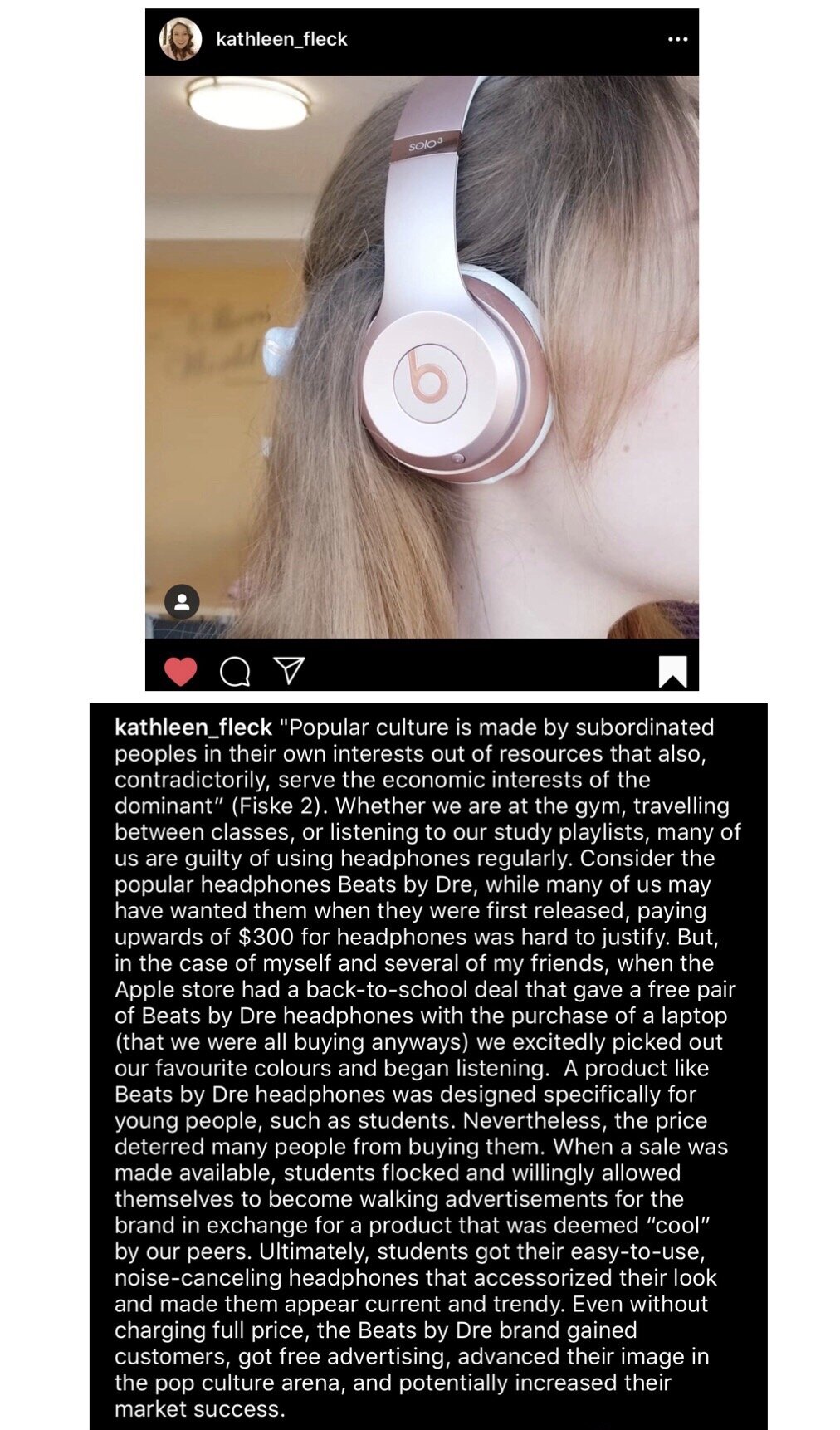

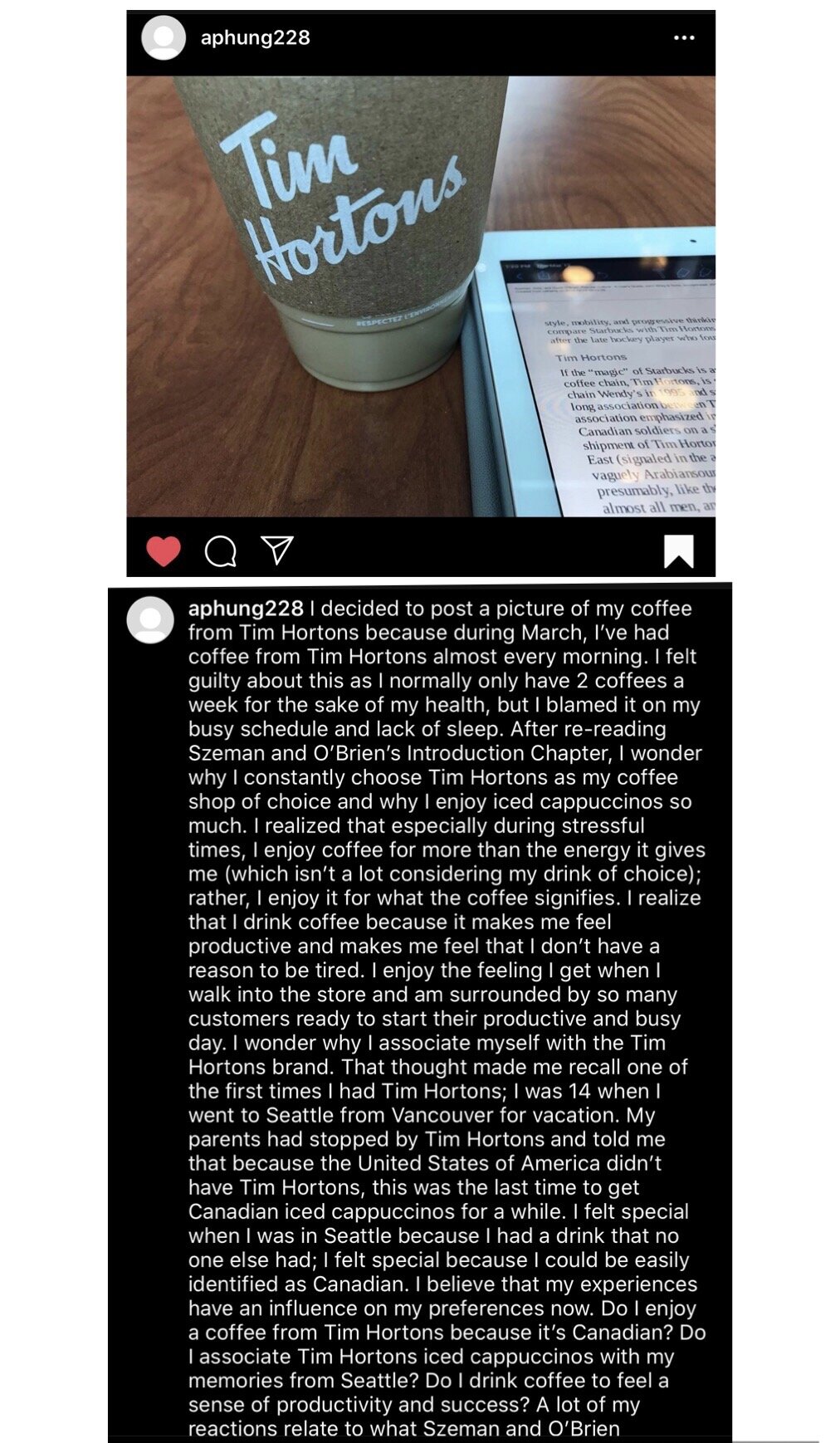

Our IG page (@pop.culture228) was initially used for another assignment, for which students had to create three original posts related to class content, readings and/or the study of pop culture. Many students applied critical definitions and concepts learned in class to reflect on their everyday rituals and practices that define their identities. I’ve asked some students to share their posts! Take a look at the photos for some great examples! (Hold and expand the text box).

If you want to view our IG page, you’ll have to add us first. The account is set to private, but once access is granted, you’ll find unique and original works by students whose passion and knowledge of popular culture is highlighted in a variety of forms, methods and thematic approaches. From paintings, to photo collages, to critical essays, to comics, to dance, to infographics, to films, and through other fascinating works of creative ingenuity, the virtual exhibition offers a glimpse into topics and texts examined in class and how students interpreted them. An image is worth a thousand words, and our exhibit showcases the importance of visual art and culture in communicating, challenging and contemplating contentious questions of culture, consumerism and capitalism in the 21st century.

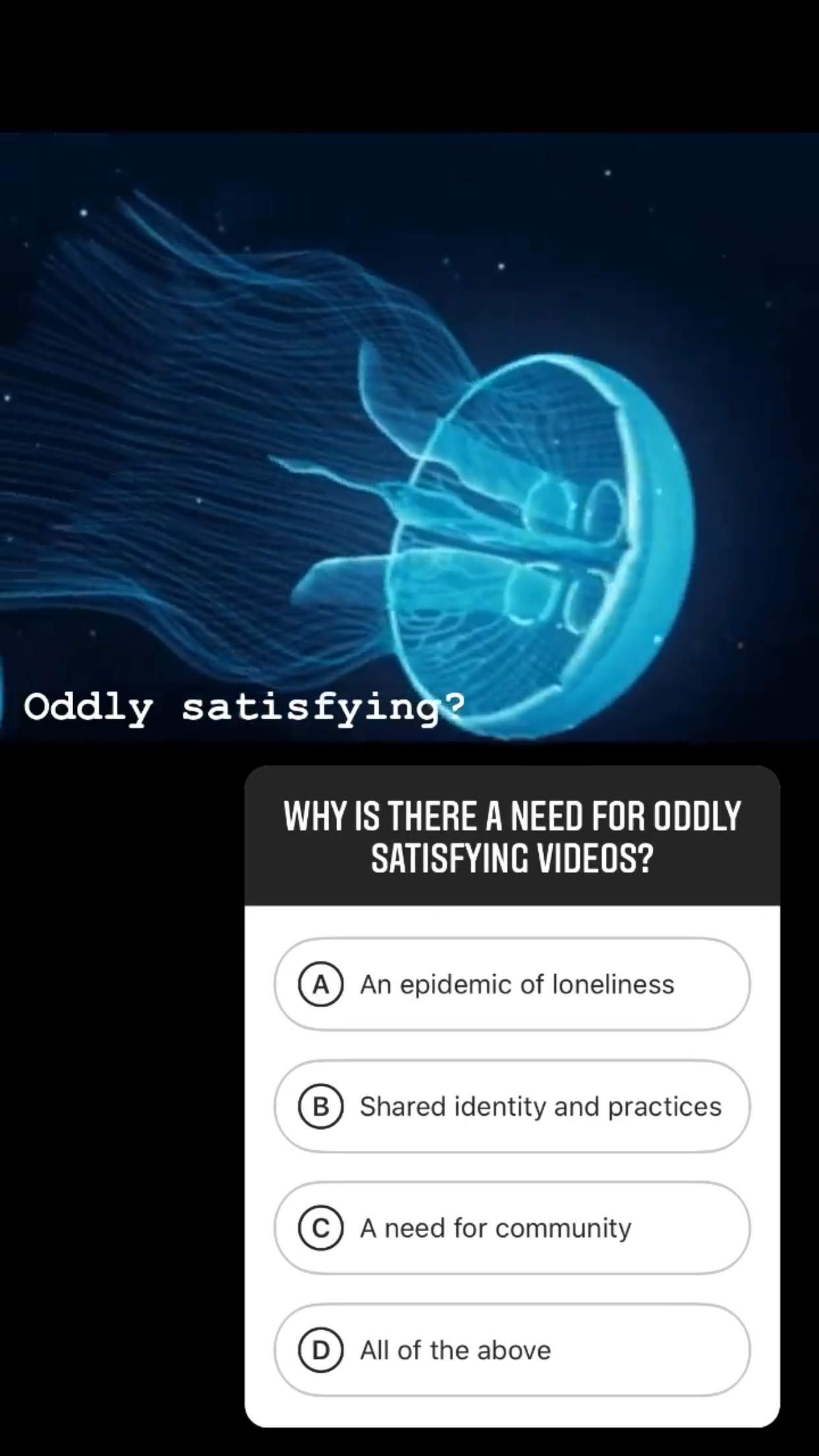

Finally, I also used Instagram to assess students’ participation by using the IG story function to create mini quizzes, on which I asked a series of open and closed questions. I thought this was a fun and interactive way to assess students’ participation and understanding of their peers’ PowerPoint presentations, which they self-studied. Check out the highlights on our IG page! (Scroll through selected images below!)

Overall, responses to taking the exhibit online were generally positive. The peer-learning portion of the exhibit was perhaps one of its most rewarding aspects, according to feedback I received from my students. The original plan was to have students ask each other about their project or essay topic in person during the first two days of the exhibit. Instead of cancelling the peer learning portion of the exhibit, I asked students to scroll through the tagged posts during class time, and to reach out to two of their classmates via DM. I encouraged students to engage in a critical discussion about their summative assignment and provided them with a worksheet to document their thoughts and findings, which was later submitted for grading. The majority of the students were genuinely interested in learning about their peer’s work(s) and I was impressed by the rigor and quality of their reflections. Although we all agree that a live exhibition would’ve been nicer in terms of seeing things with the naked eye, I’m still so proud and thankful for having such an awesome group of students who were committed until the end. I believe that when students have an opportunity to explore their own ideas and produce work that is personally meaningful to them, they thrive. This was the first time that I used Instagram as an experiential learning tool, and it worked out fantastically for this course! Most importantly, our IG page is now virtual time capsule that reflect what we currently perceive and consider as popular culture. It’ll be quite interesting to look at our IG page a decade or two from now to see how social mechanics of cultural taste have shifted over time.

Fellow instructors who’d like to see my rubric and assignment guidelines, please reach out to me here. I’d be happy to share my work and learn from you too! Again, a standing ovation to my students. As you continue to embark on your life journey, especially in times of uncertaintity, I leave you with the wise words of what Sherlock Holmes once said: “What you do in this world is a matter of no consequence. The question is what can you make people believe you have done” (A Study in Scarlet).